- Home

- Dan Callahan

Barbara Stanwyck Page 12

Barbara Stanwyck Read online

Page 12

I never saw her—except for a lunch date in 1952 that was arranged by an uncle—since she sent me away to military school in Indiana. My first year of high school. I was a bad student. I guess that bothered her. She didn’t expect me to be a genius or anything, but she wanted me to take advantage of the education she was buying for me. I didn’t. I didn’t do anything real wrong. I just wasn’t interested. I was told that she would have sent me to any college I wanted to go to. I’m sorry now that I didn’t take advantage of the offer. I guess it was more my fault than it was hers. How we each went our separate ways.

I find it admirable that Dion takes some responsibility for their rift, even if he would become more candid and embittered as the years went on and she still refused to see him. She didn’t go to his wedding. “I invited her but she didn’t make it,” he said. “She bought us a bathroom set, though. And when the baby was born, she bought furniture for him and sent us $100. It still bothers me that she’s never come to see her only grandson, my son.” Confidential magazine ran a story with Dion in 1959 with the plaintive title, “Does My Mother, Barbara Stanwyck, Hate Me?”

If she had hated him, of course, she might have come around to loving him. The truth, sadly, was that she seemed to feel almost nothing where he was concerned. Stanwyck sent him a little furniture, a little money, but her heart was closed. She kept a photo of him in her closet in later years. When he was mentioned in her presence, she would simply say, “Oh, he’s long gone,” and change the subject. Dion remembered the last time they met: “As politely as a stranger I asked about her career. As politely and distantly as the movie queen she was she answered and inquired how I had been.”

This is “star’s adopted offspring as fan,” à la Christina Crawford—a much more serious and scary case, of course, but characterized by the same sort of disconnection. As someone who loves Stanwyck as much as anyone can love an artist, I can’t really wrap my head around the fact that she could say, “You can shoot outlaw horses but not kids. The only thing you can do when you have tried everything, and nothing has worked, is to save yourself.” This, from the woman who played Stella Dallas!

Judging by most accounts, the “everything” she tried doesn’t seem to have been all that extensive. “Uncle Buck” Mack is the only one who cared at all about Dion in the Stanwyck household. At twelve, Dion was hospitalized when a fishing spear went through his leg at summer camp. “The doctors phoned my mother,” he said. “I waited and waited for her to come. She never so much as called.” At fifteen, he was something of a delinquent (anything to get some attention), and Stanwyck sat him down, with Taylor, to lecture him about his future.

Then, according to Dion, Mack drove him to Hollywood for a specific purpose: “Uncle Buck explained that Mother had paid for the high-priced call girl to teach me the facts of life.” If this actually happened, it opens an extremely dark window into Stanwyck’s psyche. I have a good friend, the writer Bruce Benderson, an outrageous, unflappable, force-of-nature fellow, and when I told him about Dion’s call girl story, even he was flummoxed. But after a pause, he burst out with, “Well, then that proves she loved him!” It was a funny line, but it contains some twisted sort of truth, I think.

Whatever led Stanwyck to do this, if she did indeed do this, it perhaps had some meaning to her that was based in her own concept of “tough love.” If we are to understand her and even some of her work, we have to come to terms with this concept, this impulse to both disillusion and enlighten. Underneath, there was probably some contempt for men and for the sex act itself, but the overarching sentiment seems to have been something like, “He needs to learn the ropes”—just as she had needed to as a girl. Nonetheless, her contempt ultimately rose to the top afterwards and stayed there. “Soon after this incident,” Dion recalled, “I got a call from Uncle Buck, and asked him if I could come home. He told me to forget it, to forget that Barbara Stanwyck was my mother. He said, ‘She wants nothing to do with you.’”

What appears to be at work here is a kind of Darwinian “fend for yourself” non-mothering mothering, mixed with a kind of desire for vengeance on the male sex and its urges, the urges that cost her those cigarette scars on her chest. And so Dion was cast out of her domain, never to return, even though he remained ever hopeful that she might reconcile with him, even on her deathbed. On that deathbed, she left instructions that he was not under any circumstances to be admitted to her room. Some of this directive might have stemmed from financial anxiety. She had forced Robert Taylor to pay her alimony until his own death as compensation for how he had embarrassed her before their divorce. Now, she didn’t want this “they shoot horses, don’t they?” old child to get a penny of her money.

So how does Dion relate to Stella Dallas, one of her key movies and the role that meant the most to her? Stella goes to great lengths to cut herself off from her daughter so that the daughter will have a chance. In life, Stanwyck went to great and on some deep level inexplicable lengths to sever all ties with her adopted son. And Ruby Stevens’s pregnant mother was hit on a streetcar by a drunk, who knocked into her so hard that she fell and hit her head and eventually died. There Ruby is, still on the steps, waiting for her dead mother to come home. So, on screen at least, Stanwyck would incarnate a mother who does everything for her child and then goes into self-imposed exile, thereby working a catharsis for Ruby and for the star’s audience. At the end, Stella is on the outside looking in at her daughter’s life, just as Dion was left looking in on Stanwyck’s real life, her career, and hoping in vain to be noticed.

Stella Dallas was a difficult shoot. Aptly enough, it was made during a make-up and hairdressing strike, so the actors had to cross a picket line every morning. Union scabs made them up and did their hair. At one point, Goldwyn came on the set and bawled everybody out; he said the rushes were terrible and that he was thinking of shutting them down. Then he looked at the footage again and phoned Vidor to say that they were doing a fine job. Vidor was and still is one of the giants of American filmmaking, but he only fitfully felt a personal connection to this material. He was probably busiest trying to fend off the stuffy unreality of Goldwyn’s production taste, the same kind of “good taste” that murders Stella herself.

As Stella’s daughter, Anne Shirley is over-eager, like a puppy bursting to do its tricks. Rehearsing the train scene, where Stella hears the truth about herself—or at least learns what the world thinks of her—Stanwyck said to Shirley, “All these years I spend in movies and I have a scene in bed with someone, and who do I end up with? YOU! Not Clark Gable, not Gary Cooper!” Her beloved crew roared at that, but this anecdote strikes me as odd. Making a joke before such an important scene is uncharacteristic of Stanwyck. Maybe the scene was so close to home that she had to somehow distance herself from it before actually doing it.

Stanwyck’s Stella is a hybrid person, a freak and a figure of fun, always tormented by her dim consciousness of failure before her ultimate failure is thrown in her face. The uneasy question of Vidor’s film is whether or not a certain type of ignorance can be so ingrained in some people that they can never really overcome it—a very un-American idea, and one at odds with the dominant mood of the 1930s. Stella’s ambition is the same ambition as those of immigrants who first came to this country chasing dreams for themselves, but mainly chasing dreams for their children. Viewed in this way, Stella is like an immigrant parent who refuses to learn English or adapt to a new environment until it’s too late.

The screenplay, written by Sarah Y. Mason and Victor Heerman, deepens and enriches Prouty’s original in many ways. In this version, Stella isn’t a compulsive flirt and doesn’t really care about male attention after her daughter is born. The more unpleasant, vain aspects of Prouty’s heroine are removed, but this removal has the effect of making Stella’s tragedy more ambiguous and more upsetting.

The film begins with a fanfare under Sam Goldwyn’s production credit, then segues into Alfred Newman’s yearning theme music. Vidor starts us in M

illhampton, Massachusetts, in 1919, and he does the whole prologue with period clothes and sets, unusual for a movie of this time. Throughout the film, but especially in the early and middle sections, Vidor uses a lot of woozy dissolves between scenes rather than hard cuts, and this technique is appropriate both for the mood of the movie and the inner life of its heroine.

We first see Stanwyck’s Stella leaving her house, carrying some books. Her hair is dyed blond for this role, so that she isn’t wearing the “evil” blond wig that always signaled she was playing murderous women. Stanwyck didn’t want to wear a wig here, she explained, because, “I couldn’t do anything with my hands, like running them through my hair. Furthermore, in her home Stella’s hair was neglected, unkempt—and that just can’t be done realistically except with one’s own hair.” Thus, Stella Dallas heralds a return to her Capra roots and to the kind of realism that powered her best work with him.

Outside of her house, Stella shyly poses and fusses to make herself look good for the men coming home from the mill, particularly Stephen Dallas (John Boles). She reads from “India’s Love Lyrics” as he passes. Her brother Charlie (George Walcott) mocks her for trying to get Dallas’s attention, then tries to kiss her himself: “Take yer dirty hands offah me!” Stella explodes, shattering the storybook visual we’ve had of her. And then we see Marjorie Main as her mother, tottling out from behind the front door and announcing, “Supper,” in a voice devoid of energy. Stella wants to get away from this life; she’s been taking business courses at night (in Prouty, and probably here, too, she turns to education to meet eligible men).

Inside the house, Stella reads about Stephen’s blighted past in the newspaper, and she reacts in a day-dreamy fashion; one of the smartest things Vidor does all through this version is to make Stella into the sort of fan that most movie audiences of the time could readily identify with. Putting down the paper, she sucks in her lower lip and thinks things over; to keep whole and untouched in her sordid environment, Stella retreats into herself and her private fantasy plans whenever she can. Stanwyck was like this in her own youth, but in her best work she was able to meld reality and daydreams, whereas the way Stella is able to totally shut out reality as a girl is one of the first strong clues to her eventual severe problems with self-deception as a woman.

As Ma Kettle Main schleps around the house, Stanwyck’s Stella looks admiringly into a mirror, fiddling idly with her hair, living in her own world. She knows that she’s pretty, and she’s something of a narcissist. When she goes to Stephen’s office to capture his interest, Stanwyck seduces him in a way completely alien to her usual style, with a simple, open smile. This is a poor girl, none too bright, but a girl with possibilities. Sitting down while Stephen is in another room, Stella lovingly feels the material of his coat, foreshadowing one of the key components of her downfall: her attraction to clothes and her stubborn lack of taste in this regard. Coco Chanel once said that a woman should get dressed and then, right before she goes out, take something off—one piece of jewelry, or one accessory. Stella Dallas will always make the mistake of stopping and putting something else on top of her outfit, a sign of her lust, the kind of lower-class lust ripe for ridicule among the polite, bourgeois society of 1919, of 1937, and today.

In the office, Stella talks to Stephen as quietly as possible. She’s almost whispery. This is the same tactic that Stanwyck tried when she wanted to bleach the Brooklyn from her voice, a parallel that shows us how perilously close she is to this role she so loved. Stanwyck makes it clear that Stella is passing in this scene, as a light-skinned black person would try to pass for white, or a lesbian would closet herself to pass for straight. Like an actress, Stella is playing a role. “I hate glasses that don’t shine, don’t you?” she asks Stephen. In most of her other movies, Stanwyck would have delivered a line like that as if she wanted us to enjoy how expertly she could con a sucker. The difference here is that Stella so desperately and sweetly wants to become the part she is playing, just as Stanwyck herself wanted to work as often as possible so that she could always be acting. She didn’t like reality and neither does Stella, but Stanwyck had an outlet and Stella does not.

Stephen and Stella go to see a silent movie, a society melodrama. As she watches the movie, Vidor films Stella’s rapt expression so that we can see just how intensely and damagingly involved she is in this early Hollywood la-la land. Her clothes aren’t too loud yet, even if there are telltale signs of fashion outrages to come: some ruffles that are slightly too large, a pattern on a robe that seems a bit too busy. As Stephen and Stella leave the theater, two girls gossip about them, and Stella snaps at them to mind their own business; so much of her later trouble will stem from prying, unsympathetic eyes. This is the fighting Stella, and it’s an open question here, sometimes, whether this need to fight has coarsened what could have been fine, or if this coarseness is rooted in her personality. Right away, she reverts to her pretensions, asking Stephen if she can take his arm: “Is that all right … is that considered …,” she asks, all in a charming rush. She stimulates the Henry Higgins in Stephen, but Boles also emphasizes how horny his character is for Stella.

“I want to be like all the people you’ve been around … educated, and speaking nice,” she says, breathlessly, as they take a nighttime walk. Cinematographer Rudolph Maté uses soft lighting here to make Stanwyck’s face appear as childlike and plain as possible, and in a scene like this, where Stella is at her most hopeful, there’s almost a feel of a Kenji Mizoguchi drama like The Story of the Late Chrysanthemums (1939), a calm and inevitable tragedy. Stella chatters about how she wants to be “like the people in the movie, all well-bred and refined.” Like so many audiences of the 1930s and after, Stella would like to live in a movie, but such a wish is as impossible as living in Stephen’s polite society, with its rules and form and regulation of emotion. Stella most wants the thing that is going to kill her (Stanwyck is heartbreaking already). And Stephen marries Stella that night because he wants to sleep with her, an unfortunate trend in this era and a convention that led to much unhappiness for men, women, and the children they bore.

Vidor jumps ahead a year. Stella has had a baby and is returning home from the hospital. Even before we see her, we can hear in her voice that something is wrong. The soft Stella that bewitched Stephen after that movie date is gone and in her place is a complacent frump-in-waiting who wants to make a splash, not because she desires male attention, as in the novel, but out of a more general kind of exuberance. Stella’s voice sounds more certain and more low-class as she climbs the stairs. When we see her, she is dressed in a bulky coat and a deforming black hat that sits on her head like a papier-mâché anvil. She talks about “kindiegarten,” and insists that she’s had plenty of experience, and she didn’t get it outta readin’ books! Vidor makes it tacitly understood that she can still hold Stephen with her sex appeal. She hasn’t quite noticed her daughter yet. Before going out, she looks at the cradle as if to say, “Ah, I like the kid, but I wanta have my fun!”

This is a new Stella, and sometimes the change in her manner is as bewildering to us as it is to Stephen, but broken, neither-here-nor-there people like Stella are always a little mysterious, especially to themselves. When she whirls around with Ed Munn (Alan Hale) at a dance, Stella is dressed in feathers and netting, and her hair is in tight blond curls. She keeps letting out the sort of high-pitched, nasal, backslapping laugh that seems designed solely to embarrass everyone in sight, but she can’t help it. This is just her nature, and Ed Munn brings this side of her out and keeps it there.

The demon Ed! Hale gives the performance of his life as this trashy galoot. Stella thinks he’s fun, which is what she’s after. And he is fun, but it’s the kind of fun that’s suited to a barroom and not a country club dance. When she wants to meet a rich man named Chandler, Stella wriggles over to his table (we see that the seat of her dress is far too tight) and gets herself introduced, employing the same softness that intrigued Stephen. At this point in her l

ife, Stella can tone down her effects when she needs to. As she ages, unfortunately, she loses this ability, and this loss is one of the saddest and one of the truest insights of Vidor’s movie.

“Gosh, I have to think every time I open my mouth!” Stella cries afterwards, when Stephen is giving her his “usual lecture.” She’s tired of playing Eliza Doolittle. Her spirit and her pride won’t let her be molded into the uptight lady Stephen wants for his wife, and you can’t blame her too much. When he tries to criticize her vulgar way of dressing, she won’t hear of it. Why, in Millhampton the girls always said she had “stacks of style,” she insists. It’s only later that we wonder if those Millhampton girls might not have said such a thing maliciously, or if they, like Stella, just didn’t know any better.

This matter of clothes isn’t a trivial issue; it can be argued that clothes alone wreck Stella Dallas’s life, even more than the id-like presence of Ed Munn. Irritated with Stephen, Stanwyck’s Stella defends herself and while she does, she scratches her head. It’s worth asking just how many actors in 1937 were scratching itches on screen, and the gesture adds a welcome touch of Brando-like realism. But it also says a lot about the character—and about Stanwyck’s preparation, for she wouldn’t have been able to scratch a wig with such abandon.

Stephen goes to New York, and Stella stays put, a development that never seems to make solid sense in any version of this story (but again, Stella so often does things out of sheer obstinacy). Some years pass and daughter Laurel is now a toddler. Stella has gotten a tad sloppy with time, but not overly so. She’s only on the first rung of her descent to the bottom, and Vidor charts this degeneration carefully. Ed Munn barges in and turns Stella’s living room into a speakeasy in about a minute flat, lighting a cigar, pouring out drinks for himself and a friend, and then scaring Laurel to death by picking her up and putting her on his lap. Stephen walks in on this scene, and Vidor gives you a shot from his point of view; we can tell that he has come in at the worst possible time. There’s no way we can blame him for wanting to keep his daughter away from Munn, but when he tells his wife that he might have to take Laurel away from her, something profound happens in Stella, and in Stanwyck’s performance. A fury rises up, crests, then falls as she pulls Laurel away from her father.

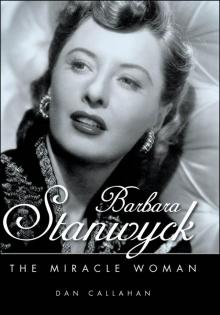

Barbara Stanwyck

Barbara Stanwyck